INSPIRE

An interview with artist Rei Naito

For someone of her stature, renowned international artist Rei Naito (like Mazda, a Hiroshima native) is surprisingly elusive. As she has no website or press team, tracking her down is no easy task, and it is only after chasing multiple art galleries and foundations that Mazda Stories finally makes contact. Naito is willing to be interviewed but would prefer to do it all via email. So I draw up my questions on her unique, challenging, inspirational work and wait with anticipation for her reply.

A week after receiving the questions, Naito sends her replies. Despite being busy opening her new show at the Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, it is clear she has taken real care with her answers. Naito’s core philosophy or question as an artist is: “Is our existence on the Earth a blessing in itself?” Regardless of the theme and message of each of her works, this question informs everything Naito does. The subtly considered themes of life and death appear regularly, and her focus on the cyclical nature of existence is emphasized by her view that “art helps people to live.”

Her installations vary in size and scope. In the same way Mazda uses natural materials in crafting its cars, Naito uses a range of items to form her art, from wooden figurines to beads, and enjoys working with “sunlight, air, gravity, water and wind.” Part of their appeal for her is that these elements “existed in this world before humans,” which helps give her work an ancient, timeless ambience.

“human” from What Kind of Place was the Earth?, 2012, installation view at Kurenboh, Tokyo. Image: Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

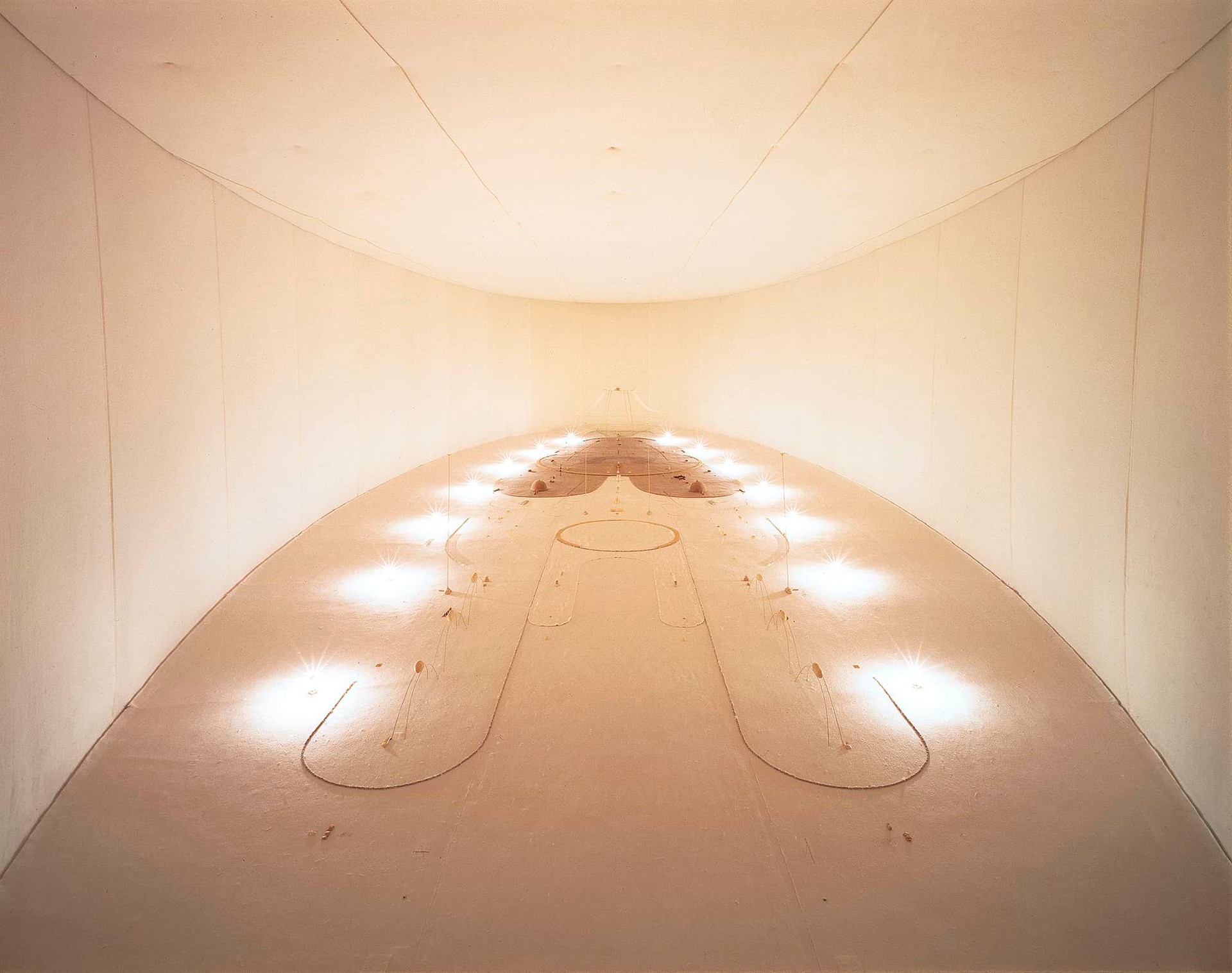

une place sur la Terre, 1991, Sagacho Exhibit Space, Tokyo. Image: Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

Being Given, 2001, Kinza, Art House Project, Naoshima, Kagawa. Image: Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

On This Bright Earth I See You, 2018, installation view at Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito, Ibaraki. Image: Naoya Hatakeyama, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

Rei Naito, 2020, installation view at Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo. Image: Kenji Takahashi, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

In her reply to one of my questions, Naito sends a list of the pieces she feels “mark her progress as an artist,” each of which is key to engendering the art that followed in a form of organic lineage. In her 1991 work une place sur la Terre (One Place on the Earth), she created an installation that you entered alone—a “maternal space”—before leaving reborn. In 1997 she created Being Called in a German monastery. Here she made a small pillow for each of the 304 dead characters featured in one of the monastery’s murals, and by “being connected to the dead in this way, I was able to connect with our existence before birth, allowing me to exist in harmony with the passage of time.”

Naito was born in Hiroshima in 1961 and remembers “gradually learning through peace education about the atomic bomb,” which is ingrained in the fabric of the city’s history. She remembers the “pride” of her primary school friend whose father worked for Mazda (then called Toyo Kogyo). She also remembers the power Mazda and the city baseball team, Toyo Carp, had in uniting “the hearts of the people of Hiroshima” as the city was painstakingly rebuilt.

Naito graduated from Tokyo’s Musashino Art University in 1985. She had studied visual communication design, but turned to creating art and was soon producing the minimalist installations that have become her calling card. She has subsequently exhibited in some of the world’s top galleries, including the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and at the Venice Biennale.

Perhaps her best known work is Matrix, her 2010 installation for the Teshima Art Museum. Teshima is a small island in the Japanese Seto Inland Sea. In the 1970s and 80s, hundreds of tons of toxic waste were illegally dumped on the island, causing significant environmental damage. Decades later the cleanup operation included the implementation of a new artwork to celebrate Teshima’s resurrection. The exterior concrete structure of the museum, nestled in the shoulder of a revived rice terrace, was created by architect Ryue Nishizawa, while Naito devised the site-specific interior installation.

Naito had been planning the artwork since 2007. Having explored nature in her 2001 installation Being Given for the Kinza Art House project, nature—and specifically water—was an increasing source of inspiration thanks to experimentation with glass bottles filled with water, aqueducts, and works that had droplets fall from the ceiling. At Teshima, Naito harnessed water to form little bubbles, rivulets and streams that seem to miraculously appear, move across the gallery floor and then disappear again.

Matrix, one of Naito’s most celebrated artworks, lives on the island of Teshima in the Seto Inland Sea. The island is part of the Chūgoku area, which includes Mazda’s hometown, Hiroshima. The region is famous for its rich manufacturing history and celebrated for pioneering the tatara method: an ancient, highly advanced steel manufacturing process. The genius of the craftsmen who developed this cutting-edge technology is manifested today in Hiroshima as a monotsukuri culture, which represents dedication to perfection and innovation in steel manufacturing. Thanks to this expertise, in the early 20th century Hiroshima became a hub for shipbuilding and automotive manufacturing, and the art of monotsukuri lives on today in Mazda’s production processes.

Top: Aerial view of Teshima Island. Image: Iwan Baan; Middle: Viewing the Matrix. Image: Iwan Baan; Bottom: Matrix, 2010, Teshima Art Museum, Kagawa. Image: Noboru Morikawa.

“Naito says that if visitors are afforded time and space to notice something small in an installation, the world will change in that moment of personal experience and revelation.”

For all the beauty and meditative peace in Naito’s works, they give away little about their creator, who remains something of an enigma. I wonder if this is because her art inspires introspection from visitors. She says that experience of her work in general “is unique to each individual.” But referencing her piece une place sur la Terre, she says the work was designed for “people to experience totally alone. The work was intended to protect and value the freedom of the heart.”

Solitude is key to Naito’s work; the majority of her installations are designed to be experienced by, at most, a handful of people at a time, and this provides the key to her message and power as an artist. She says that if visitors are afforded the space and peace “to notice something small in an installation, the world will change in that moment of personal experience and revelation. Is there anything more moving than this moment of transformation? The solitary moment may be so fleeting that it cannot be shared, but that’s precisely what makes the experience your own.”

As we enter a new year, Naito has never been busier. She has recently opened her exhibition of three-dimensional works and paintings at the Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, and her focus is now moving toward the 2021 Tokyo Biennale, her first appearance at the show. In my final question I had asked what she has planned for the event, and am delighted to hear we will see the return of the “human” from her 2012 artwork What Kind of Place was the Earth?

“human,” small figurines, will be installed in a Buddhist temple at the Biennale. Although they look broadly similar to real-life humans, they differ in that they “without a doubt, believe that whomever they see is a sign of hope.” They wait and “watch quietly for someone to appear, before welcoming them and watching over them”—a hopeful, optimistic message we could all embrace as we look to the future.

Above: the artist Rei Naito. Image: Satoshi Nagare, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery.

Words Tommy Melville

find out more

Artistic movement

Discover Mazda’s range of beautifully crafted vehicles