INNOVATE

Cutting Edge: How Hiroshima Needles Went Global

The humble sewing needle, originally used by samurai heading into battle, has a unique connection with the modern city of Hiroshima. Mazda Stories discovers more about this fascinating origin story.

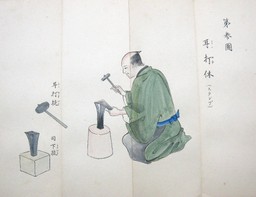

When samurai headed into battle, they carried with them one item you might not expect: a sewing needle. While not as august or fearsome as the sword, a needle was indispensable in emergencies and would be kept close at hand to repair a rip or close a wound. Originally, it was the samurai themselves who crafted the needles.

During Japan’s feudal period, the area that is today Hiroshima, where Mazda is headquartered, was ruled by the Asano samurai clan. The domain was a center of traditional steel production. While modern steelmaking relies on iron ore, at that time in Japan the primary raw material was iron sand. Using an ancient yet technologically advanced method called tatara, iron sand collected from nearby mountains was transformed into high-quality steel, suitable for making tools such as files and saws, and even the finest swords.

Taking advantage of the plentiful supply of superior steel within the domain, and to keep their samurai employed in times of peace, the clan adopted needlemaking as an official industry.

Manufacturing a needle entirely by hand was complex and meticulous work, requiring 28 different steps. The clan quickly developed a reputation for quality, and Hiroshima needles were traded widely across Japan. Mechanization began in the 19th century, after the fall of the feudal system and the introduction of Western technology, but the focus on excellence remained. Soon, Hiroshima needles were being exported around the world.

After the devastation of World War II, the Hiroshima needle industry recovered fairly quickly, in part because of strong demand for needles as people sought to replace lost household items and clothing. Efforts to rebuild also benefited from Hiroshima’s unusually good access to skilled labor.

“Because of the long tradition of steelmaking in this area, as well as shipbuilding in nearby Kure, it was possible to recruit experienced machinists to custom-build the specialized machinery needed to make needles,” says Kazuyasu Harada, Executive Director of Tulip, a producer of sewing needles, knitting needles and crochet hooks, whose grandfather established a Hiroshima City needle factory in 1948. Today, the company supplies Japanese schools with needles for home economics classes, as well as professional needleworkers and hobbyists around the world.

“The needle is such a familiar item that people may mistakenly regard it as a simple tool.”

KAZUYASU HARADA

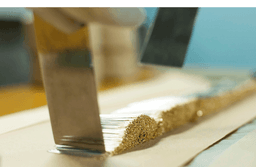

“The needle is such a familiar item that people may mistakenly regard it as a simple tool,” says Harada. “But the manufacturing process is both complex and sophisticated, requiring many different technical processes including cutting, stamping, grinding and electroplating. Hiroshima manufacturers have worked continuously to improve each process, and to create innovative needles to serve varied needs.”

As when making a fine sword, the steel is quenched and tempered, so the needle will be strong and flexible yet resistant to bending and breaking. The eye is polished inside and out for easier threading, and the point undergoes a high-density abrasive polishing treatment to ensure sharpness.

Even when a needle breaks or its tip becomes dull, it isn’t simply discarded. By long tradition, needles and pins that have outlived their usefulness are taken to temples or shrines. To ensure a “soft landing” on their way to retirement, the tiny tools are placed point-down into a smooth cake of tofu. Then, in a ritual called hari kuyō, they are thanked for their service. The custom began some 400 years ago and is still observed at certain temples and shrines around the country.

“A quality needle is much more comfortable, allowing you to sew for hours without fatigue,” says Mutsuko Yawatagaki, a renowned professional quilter and needlework instructor. “You get better results, too. Good tools make for good work.”

Words Alice Gordenker

find out more