INSPIRE

JAPANESE AESTHETICS

CONNECT THE PAST AND PRESENT

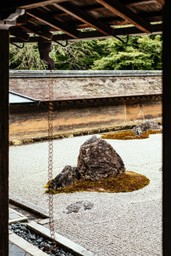

The Ryoanji temple in Kyoto, Japan, offers visitors an opportunity for self-reflection and to appreciate the distraction-free aesthetic of traditional Japanese architecture and design.

A 30-minute bus ride from Kyoto Station brings visitors to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Ryoanji, a Zen temple widely considered to have Japan’s finest example of sekitei, a dry landscape garden. Gravel is meticulously raked into patterns resembling flowing water, accented with 15 strategically placed stones that appear to float on the surface. Intriguingly, no matter which angle the garden is viewed from, all 15 stones can never be seen at once.

The rock garden of Ryoanji comprises a rectangular pebble plot with 15 stones, enclosed by low walls. Remarkably, the garden‘s design means that at least one rock is always concealed from view, regardless of the observer’s perspective.

Invitation for reflection

Azby Brown, a writer, architect, and artist who has lived in Japan for over 35 years, is the author of Just Enough: Lessons from Japan for Sustainable Living, Architecture, and Design. He points out that Ryoanji’s sekitei garden invites silent introspection, as visitors ponder the relationships between the 15 stones and the possible rationale for the groupings.

“In the process the stones simultaneously become more than just stones, while remaining simply the kinds of inert rocks found everywhere in nature. Most importantly, the design of Ryoanji, both its buildings and gardens, encourages us to pause and reflect for a few moments, and to experience something potent outside of our daily routine,” says Brown. “Much of the most ‘simple-appearing’ Japanese architecture, Ryoanji included, is actually instructing us to learn to observe the richness and complexity of the natural world.”

Opposite the stone garden is a square water basin. Its kanji characters loosely translate as “I am content with what I am.”

The gardens of the Ryoanji temple can be viewed from the hōjō, which was once the head priest’s residence.

A design revolution

These concepts in observation transcend international borders and inspire contemporary designers—including those behind Mazda’s cars. Ikuo Maeda revolutionized Mazda’s cars when he took on the role of General Manager for Design in 2009. Searching for a concept that would guide Mazda’s future, he drew on traditional wisdom of the past and connected it with car design. In a 2020 interview with The Japan Journal, Maeda explained, “When speaking of Japanese aesthetics, people often think of shoji, sliding paper doors, and bamboo. But such simplistic expression spoils their essence. We thought that we had to take the approach of spiritualism.”

Across Mazda’s newest models, “the surrounding environment is beautifully reflected on the carefully calculated surface of the exterior,” explains Akira Tamatani. “The elements have been eliminated to the utmost, to create yohaku.”

How less becomes more

Maeda recognizes the appeal of emptiness from Zen and Ryoanji’s garden, which draws on the traditional Japanese concepts of ma (interval or space) and yohaku (empty space). While Western sensibility usually seeks to fill spaces and silence, the opposite is true with Zen.

“Ma and yohaku are sensibilities of emptiness which call attention to the relationships among things that exist in the real world, and by extension, in the aesthetic and spiritual worlds,” notes Brown. “Both ma and yohaku are connected to Zen Buddhist concepts of transformative emptiness—the beauty of nothingness.”

Blurring the boundaries between what is there and what is not, these traditional concepts are now being incorporated into international architecture and interior design, lending a characteristically Japanese aesthetic. In a similar vein, Mazda’s philosophy is based on the beauty of subtraction, homing in on the design theme and bringing it center stage. To this end, ma and yohaku are integral to car design, too.

Design in a new light

“Based on these concepts, design can stimulate the viewer’s imagination and appeal to the senses, allowing the features the designer wants to emphasize to stand out more strongly,” says Akira Tamatani, Chief Designer of the Mazda CX‑60. “The car’s exterior surface, where all superfluous elements have been eliminated, is like the ultimate expression of yohaku, or blank space, with the surrounding environment reflected on its surface.” In this way, the overall expression of beauty goes beyond that of just the car, allowing it to be considered in the greater context of its surroundings.

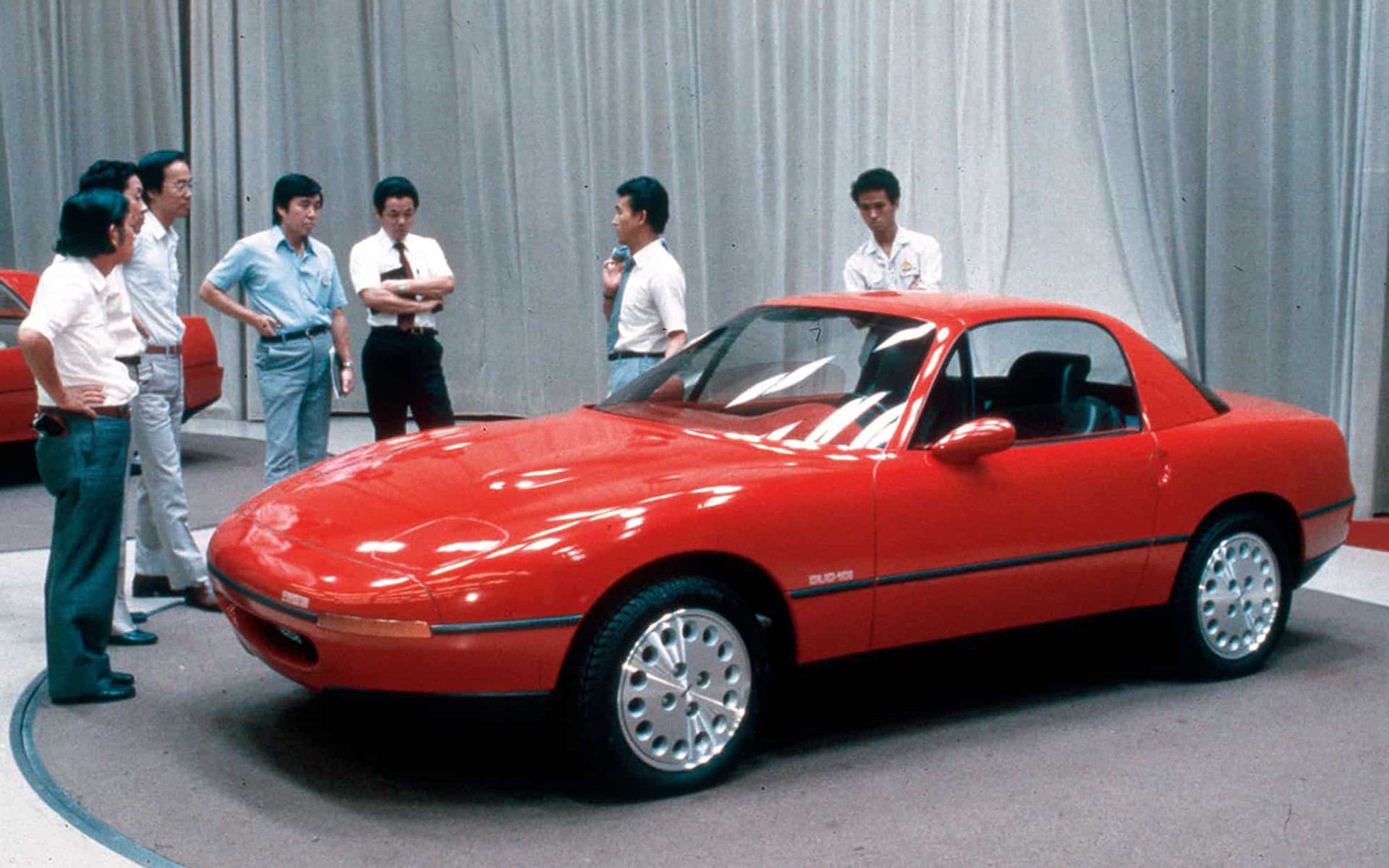

The Mazda Vision Coupe, pictured above, expresses the essence of Japanese aesthetics and won “Most Beautiful Concept Car of the Year” at the 33rd Festival Automobile International.

“On the inside, elements in the car’s interior are arranged in an extremely precise manner to create ma, or space, where the light coming in from outside the car is fully utilized,” says Tamatani, noting that Ryoanji serves as a great example of Japanese aesthetics and the expression of light. “Light connects to the passing of time and the changing of the seasons in the garden. Similarly, our design uses light not only to enhance both the car’s exterior shape and interior space, but also to express the passing of time at any given moment; through the surrounding light reflected on the surface of the car, or shining into the interior,” he explains.

Authentic appeal

In contrast to industry design trends that focus on strength of expression and impact, Mazda continues to draw on Japan’s classic sensibilities. “I feel that our cars particularly appeal to people who are attracted to and value this authenticity in manufacturing, based on traditional Japanese aesthetics,” says Tamatani.

The timeless qualities of Japanese design offer valuable opportunities for reflecting on and connecting with our surroundings, while making new discoveries in the process. They can be found everywhere from contemplation in a centuries-old stone garden at Ryoanji to Mazda’s newest cars—the reflections on the Mazda3, for example, convey a sense of tranquility and can change depending on where the car is and the time of day. Small wonder it was crowned the World Car Design of the Year.

Words Louise George Kittaka / Images Mark Parren Taylor

find out more